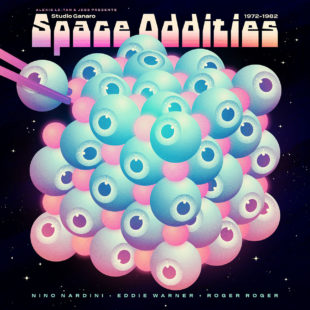

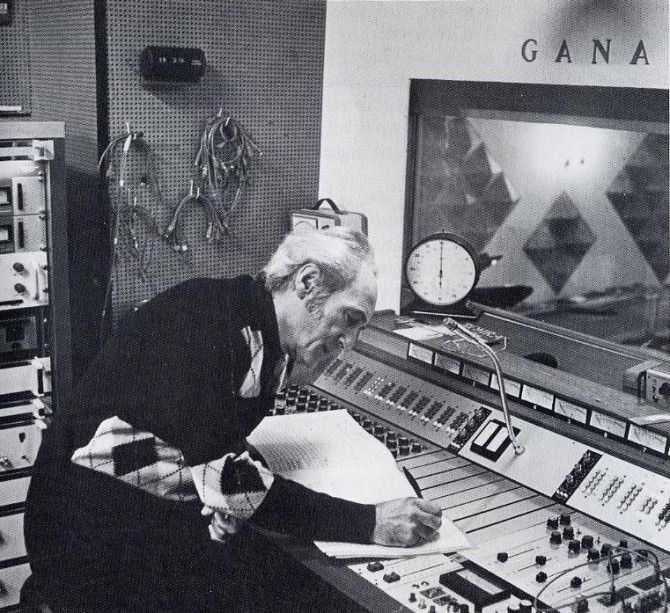

C’est à l’aube du XXème siècle que Roger Roger et Georges Achille Teperino voient le jour. Roger en 1911 à Rouen, Teperino à Paris l’année suivante. Ce sont des enfants de la balle, la mère de Roger est cantatrice, son père chef d’orchestre à l’Opéra, Teperino suit l’enseignement de son géniteur d’origine italienne violoniste et compositeur. Roger et Georges se rencontrent au lycée en 1927 et vont devenir les meilleurs amis du monde (Roger épousera même en première noce la mère de Teperino qui deviendra de fait son beau fils) en formant un orchestre baptisé Les diables rouges pour animer les bals du samedi soir et les clubs ou l’on swingue. Pour l’occasion Teperino prend un pseudo qui fera sa renommée : Nino Nardini. Après la seconde guerre mondiale Nardini se spécialise dans la musique exotique en montant un orchestre, le Nino Nardini orchestra, qui enflamme les dancings où les adolescents flirtent et virevoltent sur du paso doble, du fox trot, de la calypso, du slow rock, du cha cha cha ou du tango. Parallèlement il dirige un orchestre de Radio Luxembourg mais aussi celui d’un cirque itinérant, suivant au millimètre les numéros d’équilibristes, de clowns ou de dresseurs de lions. De son coté Roger Roger (c’est son vrai nom) travaille aussi comme chef d’orchestre à Radio Luxembourg et accompagne Edith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier, Jean Sablon ou Charles Trenet sur scène. Radio France le sollicite alors pour enregistrer certaines de ses compositions pour illustrer ses programmes. Des mélodies qui attirent l’attention des éditions Chappel à Londres qui viennent d’ouvrir un département spécialisé dans les musiques d’ambiance, des musiques vendues « au kilomètre » à la radio, à la télévison ou au cinéma. Roger Roger fait ainsi ses débuts dans l’illustration sonore dont il va devenir l’une des figures emblématiques par la profusion et l’éclectisme de ses productions, mais surtout par son gout prononcé pour l’expérimentation. Nardini le rejoint très vite dans ce qui apparaît comme un nouvel eldorado. Ensemble les deux compères font exploser les rigidités de la tradition française en intégrant dans leurs compositions des instruments inattendus comme le clavecin, le marimba ou l’ondioline et, dès qu’ils apparaissent, les premiers synthétiseurs analogiques, oscillators et autres claviers électroniques. Sous le feu de l’innovation sonore, Nardini se passionne au début des années 60 pour la musique concrète telle que professée par Pierre Schaeffer (qui vient de fonder le GRM), popularisée par Pierre Henry ou twistée par le fantasque Jean Jacques Perrey. Par désir d’indépendance Roger et Nardini décident alors de créer leur propre studio à Jouy-en-Josas dans la vallée de Chevreuse avec la complicité de Francis Gastambie, en charge de la partie commerciale. Baptisé Ganaro, acronyme des deux premières lettres de leurs noms de familles respectifs, le studio devient le théâtre de sessions nocturnes aussi joyeuses qu’expérimentales où se joint leur ami Eddie Warner. L’acquisition d’un moog est un véritable détonateur pour ces pionniers de la musique électronique, Roger Roger fabricant lui même ses cartes perforées afin d’inventer de nouveaux sons. C’est ainsi qu’en 1969, sous le pseudonyme de Cecil Leuter, il publie les albums Pop Electronique et TVMusic 101 (avec Nardini), deux ovnis « 100% électronique » qui anticipent l’hégémonie à venir des machines dans la pop musique, le space disco de la fin des années 70 comme l’électro funk du début des années 80. Véritables stakhanovistes de l’illustration sonore le duo va composer plus de 40 albums pour les labels spécialisés Chappel Music, Southern Library Of Recorded Music, Neuilly, IM (le label d’Eddie et Hanelore Warner qui publiera notamment The Strange World of Bernard Fèvre en 77), Mondiophone, Hachette, Musax ou Crea Sound Ltd. Une véritable atlantide de la musique électronique qui sera redécouverte au tournant du siècle par des artistes électroniques comme Barry 7 d’ Add N to (X), avec la série des Connectors ou Luke Vibert, avec la compilation Nuggets. Jess et Alexis Le Tan apportent ici leur pierre à l’édifice en exhumant les pépites surgies du Studio Garano, des morceaux composées avec allégresse et humilité par un joyeux trio de sexagénaires pour qui la création musicale a toujours été une source d’amusement et d’émerveillement. Nino Nardini a disparu en 1994, Roger Roger en 1995. Eddie Warner les avait quitté quelques années plus tôt. Dans sa villa de Neuilly, sa veuve Hanelore Warner évoque pour nous le souvenir de son mari et de ses amis.

Comment avez vous rencontré Eddie Warner ?

Nous étions tous les deux d’origine allemande. Je faisais alors des études de traduction littéraires à Paris. On s’est rencontré en 1965 sur les Champs Elysée, au cinéma, le film s’appelait « Rencontre », puis l’aventure a continuée…

Quel était alors le parcours de votre mari?

A l’arrivée d’Hitler au pouvoir, mon mari, né en 1917, a du quitter l’Allemagne. Comme il était très doué pour la musique, l’organisation juive de Berlin lui a trouvé une place au conservatoire de Strasbourg où il a continué ses études de piano et trompette. La situation s’est aggravée et il a du fuir vers l’ouest, à Paris où il était un refugié comme il y en a aujourd’hui des milliers : sans papier et sans travail. Son frère, son père et sa belle-mère l’on ensuite rejoint. La mère de mon mari était chanteuse d’Opéra, son père était le premier assistant de Furtwängler, le grand chef d’orchestre allemand avant Karajan. Pour gagner un peu d’argent Eddie, son frère et son père ont monté une petite formation pour jouer dans les brasseries et gagner un peu d’argent, puis le frère est parti dans un kibboutz en Israël. Mon mari s’est alors retrouvé seul à Paris gagnant difficilement sa vie comme répétiteur pour des danseuses ou des chanteurs, il s’est alors engagé dans la légion jusqu’à la fin de la guerre où il est devenu clairon. Après guerre il jouait du piano dans les boites de nuit parisienne, comme il y avait beaucoup de soldats américains dans ces clubs qui lui demandaient de jouer des morceaux de jazz, il a su s’adapter car il avait l’oreille très musicale, un jour l’un d’eux, lui a demander de jouer une samba et c’est parti comme ça. Il a crée son orchestre de musiques tropicales composé de 17 musiciens payés à l’année, ils jouaient principalement dans des bals et il fallait tout le temps trouver des dates et des engagements sur des enregistrements de disques car il voulait toujours conserver la même formation. C’est à ce moment qu’il a fait la rencontre de Lalo Schifrin qui tournait avec une formation d’Amérique du sud, qui était réfugié, et qu’il a engagé comme musicien et arrangeur dans son orchestre en l’aidant à obtenir ses papiers.

C’est à ce moment que votre mari enregistre ses premiers disques ?

Oui dans les années 50 chez Odéon. À l’époque l’ORTF avait homologué des orchestres qui jouaient en live à la radio. Eddie avait des commandes, composait et arrangeait pour son orchestre. Les bandes appartenaient à l’ORTF. Il était encore tout le temps en tournée avec son orchestre, ils faisaient des bals les samedi soirs dans toute la France mais également dans le monde. Il donnait aussi bien des concerts au Liban, en Afrique du Nord, Allemagne ou en Belgique. À Madrid, il a fait la connaissance de Lionel Hampton, il se sont amusé à diriger leurs orchestres respectifs puis ils ont fait un disque ensemble chez RCA.

Comment nait IM, votre label d’illustration sonore ?

A un moment donné, il a été assez déprimé par la scène, la fatigue des tournées. Il a eu un très grave accident de voiture en Afrique du Nord, il a eu une double fracture des hanches et la main droite complètement cassée. Suite à sa longue convalescence, il ne pouvait plus jouer très longtemps du piano, il écrivait pour des chanteurs, les accompagnait parfois. Mais il en avait marre, il ne voulait pas vieillir sur scène. On a donc crée ensemble des éditions d’illustration sonore. C’est comme ça qu’est né IM au début des années 60, à moi l’organisation, à lui l’artistique. On représentait également des library anglaises comme KPM, très jazzy, grand orchestre, pas du tout du gout français, il manquait donc quelque chose. L’arrivée des instruments électroniques a été un déclic en particulier dans le studio Ganaro de Roger Roger à Jouy-en-Josas. Roger Roger était dans la library depuis longtemps. Il travaillait principalement pour les anglais et en avait également marre des grands orchestres. Eddie, Roger et Nardini se connaissaient depuis longtemps. Les disques sont nés au début par fun puis plus sérieusement. C’était assez étonnant de voir ces musiciens au background classique issu de familles de musiciens professionnels avoir la curiosité de faire connaissance avec de la musique qu’on peut programmer, de se frotter à des sonorités insolites, de voir jusqu’où ils pouvaient pousser ces nouveaux instruments. Quand on partait en vacances en camping car, mon mari avait acheté un piano portatif qui marchait avec des piles et pouvait tenir sur un trépied. A la plage, il posait ainsi son piano électrique à coté de sa serviette et composait.

Ils étaient à l’affut de tous les nouveaux instruments qui apparaissaient ?

Oui constamment, c’était un vrai investissement. La première boîte a rythme coutait très cher, et ils étaient donc exigeants. Leur studio était bourré de nouveaux instruments, il y avait des fils partout, pour moi c’était assez angoissant (rires) Ils travaillaient surtout le soir parce qu’ils étaient tranquilles, sans téléphone. Ils redevenaient alors de grands enfants, ils n’arrêtaient plus, il y avait un vrai goût pour l’expérimentation, pour les découvertes sonores liées aux instruments électroniques qu’ils essayaient alors de maitriser. Ensuite ils faisaient une sélection parmi les morceaux enregistrés pour sortir des disques.

Est ce que vos clients, que cela soit la télévision, la radio ou le cinéma, étaient à la recherche de ces sonorités avant gardistes ?

Oui parce que cela donnait un nouvel impact aux images qui pouvaient ainsi être plus captivantes pour les spectateurs. Avant la musique remplissait trop l’espace, mais désormais on était en plein dans l’ère industriel, il fallait imiter le son des machines, des premiers robots. Je pense que c’était dans l’inconscient collectif de vivre dans la modernité, c’était l’ère de la conquête spatiale.

Est ce que l’explosion du rock et de la pop musique à la même période intéressait votre mari?

Oui et non. Au début les Beatles ne lui plaisaient pas du tout. Après il a reconnu la musicalité des morceaux, leurs grandes mélodies. Mais ils incarnaient aussi pour lui la fin de la vie des orchestres et des bals et l’apparition des disc jockeys qui animaient les soirée avec des disques. C’était la fin d’une période et l’apparition d’une autre. Le jazz restait sa grande passion et il continuait à faire le bœuf : il partait le soir jouer dans les clubs avec ses amis musiciens.

Comment leur aventure musicale se termine ?

Les derniers disques sont sortie à la fin des années 70, le genre s’est éteint progressivement car les morceaux qui sortaient devenaient une imitation de ce qui c’était fait avant. Ils auraient pu continuer encore longtemps mais mon mari est mort en 1982.

Comment expliquez vous que dans un processus fonctionnel, l’illustration sonore, ils ont crée quelque chose d’aussi libre ?

Parce qu’ils ne pensaient pas à l’argent et faisaient de la recherche sans jamais se prendre au sérieux. Grâce à cette attitude, ils ont réussi à capter l’attention à l’étranger. Leurs disques ont ainsi été distribués en Angleterre et aux Etats-Unis qui en ont fait des imitations. Ils ont vraiment incarné un rupture : celle du passage des instruments traditionnels à l’électronique.

texte : Clovis Goux

///////////////////////////////////////////

///////////////////////////////////////////

Translation : Jon von Zelowitz

During the 60s and 70s, three distinguished old gentlemen who had built their careers playing “made in France” exotic jazz – Roger Roger, Nino Nardini and Eddie Warner – met every evening in the Ganaro recording studio, playing like kids with their new toys: souped-up keyboards that looked more like prototypes of spaceships to explore the Milky Way. Flying high on whimsical and joyful inspiration, the improbable trio used their strange instruments to sketch out the beginnings of something that, at that time, resembled the future of music. Let’s take a trip with them toward a pop, light-hearted and electronic future.

At the dawn of the twentieth century, Roger Roger and Georges Achille Teperino entered the world. Roger was born in 1911 in Rouen; Teperino the year after in Paris. They followed in their parents’ footsteps. Roger’s mother was a singer, and his father conducted the orchestra at the Opera. Teperino was taught music by his father, an Italian violinist and composer. Roger and Georges met in secondary school in 1927 and became the very best of friends, to the extent that Roger’s first wife was Teperino’s mother, making the latter his son-in-law. They formed a band called Les Diables Rouges (The Red Devils) that played halls and nightclubs where people would swing dance. For the band, Teperino adopted a nickname that made him famous: Nino Nardini. After World War II, he formed the Nino Nardini orchestra, specializing in “exotic” musical styles. They set the dance floors on fire in the clubs where young people, when not flirting, would twirl to the paso doble, foxtrot, calypso, slow rock, cha-cha and tango. At the same time, he conducted an orchestra for Radio Luxembourg, and one in a traveling circus, providing closely-tailored accompaniment for acrobats, clowns and lion tamers. For his part, Roger Roger (his real name) also worked as a conductor at Radio Luxembourg and accompanied Edith Piaf, Maurice Chevalier, Jean Sablon and Charles Trenet on stage. Radio France asked him to record some of his compositions as production music for its programs. These melodies attracted the attention of Chappell & Co., a music publisher in London that had just opened a department specializing in library music, which they sold “by the ton” to radio, television and cinema. Roger thus made his debut in production music. He was to become an emblematic figure in this domain, for the profusion and eclecticism of his productions, but, above all, his pronounced taste for experimentation. Nardini soon joined him in what appeared to be a new Eldorado. Together the pair made a clean break with rigid French traditions, via compositions featuring unexpected instruments like the harpsichord, marimba and Ondioline. Later, when the first analog synthesizers, oscillators and other electronic keyboards appeared, they were adopted as well. Always seeking innovative sounds, Nardini got deeply into concrete music in the early 60s, as put forward by Pierre Schaeffer (who had just founded the GRM, Groupe de recherches musicales), popularized by Pierre Henry and twisted by the whimsical Jean-Jacques Perrey. Seeking independence, Roger and Nardini decided to create their own studio in Jouy-en-Josas, southwest of Paris. They handled the creative side, while Francis Gastambie took care of the business end. The studio was named “Ganaro,” an acronym of the first two letters of their respective family names. It became the scene of magical nightly sessions of experimentation, in the company of their friend Eddie Warner. The acquisition of a Moog synthesizer brought these pioneers of electronic music to a new level. Roger Roger manufactured his own punch cards to invent new sounds. Then, in 1969, under the pseudonym of Cecil Leuter, he published the albums Pop Electronique and TVMusic 101 (with Nardini), two truly avant-garde “100% electronic” disks that anticipate the hegemony of machines in pop music, from space disco in the late 70s to the electro funk of the early 80s. With a Stakhanovite output of production music, the duo composed more than 40 albums (including the incredible Informatic 2000) for specialized labels: Chappell Music, Southern Library of Recorded Music, Neuilly, IM (Eddie and Hannelore Warner’s label, which published, notably, The Strange World of Bernard Fèvre in 77) Mondiophone, Hachette, Musax and Crea Sound Ltd. A veritable Atlantis of electronic music, rediscovered at the turn of the 21st century by electronic artists like Barry 7 of Add N to (X), with his Connectors series, or Luke Vibert, with the Nuggets compilation. Jess and Alexis Le Tan contributed a bit as well, digging up a few gems from “Ganaro’s Nights,” tracks composed with joy and humility by a merry trio of sixty-somethings for whom making music was always a source of amusement and wonder. Nino Nardini passed on in 1994; Roger Roger in 1995. Eddie Warner (the fortunate composer of the theme song for the TV game show “Des chiffres et des lettres”) had died a few years earlier. In her villa in Neuilly, a posh Paris suburb, his widow Hannelore Warner evoked the memory of her husband and his friends.

How did you meet Eddie Warner?

We were both born in Germany. I was studying literary translation in Paris. We met in 1965 on the Champs Elysées at a cinema. The film was called “Rencontre” (Encounter) and the adventure continued afterward…

Tell us about your husband’s life.

When Hitler came to power, my husband, born in 1917, had to leave Germany. As he was very gifted in music, a Jewish organization in Berlin found him a place at the Strasbourg Conservatory in eastern France, where he continued studying piano and trumpet. The situation worsened and he had to flee further west, to Paris, where he was a refugee, just as there are thousands today: undocumented and without work. His brother, father and stepmother joined him there afterward. My husband’s mother was an opera singer; his father was the first assistant to Furtwängler, the great German conductor who preceded Karajan. To earn a little money, Eddie, his brother and his father put together a small band to play in bars. Later, his brother moved to a kibbutz in Israel. My husband thus found himself alone in Paris, barely earning his living as a tutor for dancers and singers. He enlisted in the French Foreign Legion until the end of the war, where he became a bugler. After the war he played the piano in Paris nightclubs. There were many American soldiers in these clubs who requested jazz numbers. Since he had a very musical ear, he was able to adopt that style. One day a soldier asked him to play a samba, which led to his next evolution. He created an orchestra to play Latin music from the Caribbean, composed of 17 musicians paid on an annual basis. They played mainly in dance halls. He was obliged to fill his calendar with concert dates and recording sessions because he wanted to retain all the same musicians. That’s when he first met Lalo Schifrin, then a refugee touring with a South American band. Eddie hired Lalo as a musician and arranger for his orchestra, while helping him to obtain his papers.

And that’s when your husband cut his first records?

Yes, in the 50s, for the Odéon label. In those days, the ORTF (the French national radio) had a few orchestras that they worked with constantly to supply music for their programs. They hired Eddie, and he composed and arranged music for his orchestra. The recordings belonged to the ORTF. He was still touring non-stop with his band. They were playing at dance halls on Saturday nights throughout France, and even in other countries worldwide. They played in Lebanon, North Africa, Germany and Belgium. In Madrid, he met Lionel Hampton. For fun, they took turns conducting each other’s orchestra, and then they made a record together for RCA.

How did IM, your production music label, get started?

At one point, live performances and touring were tiring him and getting him down. He had a very serious car accident in North Africa. He had a double fracture of the hip and his right hand was completely broken. Even after a lengthy convalescence, he could not spend long sessions on the piano. He wrote for singers, and sometimes accompanied them. But this was bothering him. He did not want to grow old on stage. So, together, we published production music. That’s how IM began, in the early 60s. I took care of business and he handled the artistic side. We also represented the English libraries like KPM: very jazzy, big bands, not at all corresponding to French tastes, so there was something missing. The arrival of electronic instruments, in particular, catalyzed something in Roger Roger’s Ganaro studio in Jouy-en-Josas. Roger Roger had been creating library music for a long time. He had been mainly working for the English and he, too, was tired of the big bands. Eddie, Roger and Nardini had known each other for years. The first disks were made for fun, and then things became more serious. It was rather amazing to see these musicians, with a classical background, from families of professional musicians, having the curiosity to get into music that can be programmed on a machine, to play with unusual sonorities, to see how far they could push these new instruments. When we left on vacation with a motorhome, my husband bought a portable piano that ran on batteries and sat on a tripod. At the seaside, he set up his electric piano next to his beach towel and composed.

Were they on the lookout for new instruments that appeared?

Yes, constantly. And they invested a lot of money in them. The first rhythm box cost a fortune, they really insisted on getting all the latest stuff. Their studio was chock full of new instruments, there were wires everywhere, it was pretty scary for me (laughs). They worked mostly at night because it was quiet, there were no telephone calls. They were like big kids, they never stopped, they loved experimentation, discovering the sounds they could get from the electronic instruments they were trying to master. Then, they selected some of the songs they recorded and released them on records.

Were your customers, whether television, radio or cinema, actually looking for these avant-garde sounds?

Yes, because it gave the images a new impact, making them more exciting for the audience. Previously, the music had filled the space too much. Now, we found ourselves immersed in the industrial era, where we had to imitate the sound of machines, of the first robots. I think it was in the collective unconscious that we were living in a modern era, the era of space exploration.

Was the explosion of rock and pop music, during the same period, of interest to your husband?

Yes and no. At first, he did not like the Beatles at all. Later, he recognized the musical quality of the songs, their superb melodies. But they also embodied for him the end of orchestras and dance halls and the appearance of dances where DJs played records. It was the end of one era and the beginning of another. Jazz remained his great passion and he continued to participate in jam sessions. He took off in the evenings to play in jazz clubs with his musician friends.

How did their musical adventure come to an end?

The last records appeared in the late 70s. The genre died out gradually because the tracks that came out later were becoming quite similar to previous ones. They could have gone on, but my husband died in 1982.

How do you explain that, in the context of making production music, which is normally nothing more than a commodity, they created something so free?

Because they were not thinking about the money and they were trying things without ever taking themselves seriously. With this attitude, they managed to capture attention abroad. Their records were distributed in England and the United States, and gave rise to imitators. They truly embodied a breakthrough: the transition from traditional instruments to electronic ones.